I have been rediscovering my security risk management roots recently and developing the components of a quantitative approach to security risk management. I am picking up the risk books I put down in 2008 when Cyber became the new brand for information security. At that time I became much more focused on understanding and implementing the new controls and practices that emerged.

Something I often noticed when I was consulting, and when I was reviewing a colleague’s security risk assessments, was that the choice of risks was often driven by a combination of hard-won experience in past incidents and regulatory reviews as well as by the hard marketing of vendors keen to force the prioritisation of their product over the thousands of competitors. Availability bias meant that we often focused on those issues that we could most easily remember and as a result heavily-weighted our focus towards them.

As a result, we were often chasing our tails, managing past risks (or risks that didn’t necessarily apply to us) rather than ensuring we were looking to the future risks we did or would face. Inevitably this led to security incidents that surprised us, either by the vector in which they started or the scope of what they impacted.

As I so often do I went back to some of Dan Geer’s thinking, this time from his keynote to the Recorded Future Conference in 2015 where he introduced a definition of security that is hard to disagree with. Dan describes security as “The absence of unmitigatable surprise.“. It’s a surprisingly simple sentence that requires some unpacking.

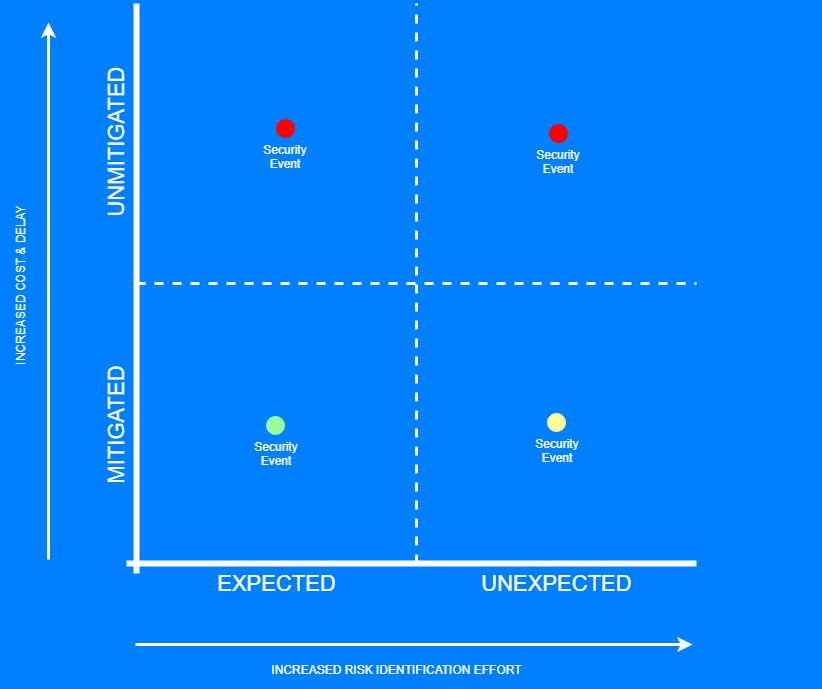

We should hope that our security events fall into both expected and mitigated. Expected events relate to the general class of event rather than the specific instance and mitigated being the state of having taken some action to reduce the frequency and harm of the event (Note mitigated not eliminated).

If we get lucky our security controls have broad applicability and an unexpected security event occurs but is similarly mitigated by our unknowing actions to manage different risks.

However, we do not have unlimited resources of money or time, which means we may end up subject to expected but unmitigated events. These are the risks that we know we need to manage but are number 6 on a top 5 list or number 11 on a top 10 list when the budget is being discussed.

These are bad, in that to external eyes, we appear to have not addressed a risk we were aware of which if wholly true is looks like negligence. But, in a well-governed environment, it is the decision of the broader leadership team as to how much risk they are comfortable taking and as a result how many resources to apply to mitigate them.

If we (and they) are well informed and make a rational economic decision then it isn’t negligence, it is risk-taking (An interesting conversation to have post-facto with a lawyer or a regulator).

What has the potential to be truly bad both in terms of harm outcomes and regulatory/legal outcomes is the risk we don’t see coming that we have not mitigated by our existing controls, The unexpected AND unmitigated security event. Because we have had no chance to limit frequency or harm and because we have had no chance to at least prepare for what we will do then the event will likely cause its full measure of harm, and we will likely be at best inefficient in handling it.

So how do we avoid unmitigated surprises?

We need to consider the full scope of the risks we are facing. Being comprehensive in considering future risks is not a new problem and the wider Enterprise Risk Management, and Operational Risk Management disciplines have a similar requirement. They have addressed this through the development of ‘Risk Universes’. Traditionally these were just a taxonomy of risk components that would look very familiar in approach to security risk managers.

More modern approaches [PDF] to Risk Universes are structured about the sources, events and consequences of risks and are more aware of the risk factors. This chimed with the work I had done with Carl Young at Stroz Friedberg so I have developed an Information Security Risk Universe to guide risk identification. I will cover this in more detail in my next post.

1 thought on “Unmitigated Surprise and Why Robust Risk Identification Matters”

Comments are closed.